1.4.22 Perplexing Presentations (PP) and Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII) in Children

SCOPE OF THIS CHAPTER

Concern may be raised when a child presents in an unusual way. They may have unusual symptoms, or not respond as expected to usual management, or present unusually frequently. At this stage there are a number of possibilities including:

- True medical cause

- Overanxiety, inexperience or mental illness in parent affecting their perception of child's symptoms

- "True" fabricated or induced illness, a potentially serious diagnosis.

The presentation is "perplexing". We need to establish the cause, and in particular consider the possibility of fabricated or induced illness by the carer. The aim of this pathway is to help in that assessment.

It is important to keep the focus on the harm to the child, and protecting the child from that harm, rather than on parental actions and motivations. Understanding parental motivation is not essential to making a diagnosis of FII.

This is a multi-agency guideline, because although presentations most commonly occur in health, concerns may also arise in any agency working with children and families, and require a shared understanding of the issues, and a multi-agency response. The aim is that where FII is occurring, it is recognised and children's welfare safeguarded.

It is necessarily detailed as it reflects the often highly complex nature of this form of abuse, and the particular challenges for all professionals in terms of recognising and responding to possible FII.

Guidance is also provided for practitioners working with lower-risk presentations where there may be a phase of uncertainty during which FII cannot be easily ruled in or out.

How has this guidance changed from the last version published in 2019?

The main changes have been to align it more closely to the RCPCH guidance published in 2021. We have kept the Red and Amber pathways, which do not feature in that guidance, but map closely to it, and remain a useful shorthand for distinguishing between the two main approaches. The Red Pathway applies when FII is probable and there is high risk of harm; the Amber when the situation is one of a Perplexing Presentation, where FII is being considered. We have revised the alerting signs to be the same as in the RCPCH guidance, and included reference to medically unexplained symptoms. We have introduced a new emphasis (in the Amber pathway) on reaching consensus through a multi-professional meeting, agreeing a Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan, and working collaboratively with parents. We have placed less emphasis on chronologies, which should not delay proceedings, but still have an important role.

| Also refer to Appendix C: Red and Amber Pathways |

AMENDMENT

This chapter was revised throughout in June 2022.1. Introduction

'The common starting point for concern about Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII) is that the child's clinical presentation is not adequately explained by any confirmed genuine illness, and the situation is impacting upon the child's health or social wellbeing" [1]. In FII, the child suffers harm through the misleading, erroneous or deceptive report or action of a parent/carer, so that the child is presented as ill when they are not ill, or more ill than is actually the case. The term 'perplexing presentation' is used at the early stages when a child first presents, or when other possibilities for the presentation are possible.

FII is based on the parent's underlying need for their child to be recognised and treated as ill, or more unwell/more disabled than the child actually is (when the child has a verified disorder, as many of the children do). This need is thought to arise from two motivations: 1) parental gain (e.g. from sympathetic attention); 2) parental erroneous beliefs (e.g. mistaken beliefs about their child's needs or health). Either way, the child comes to harm.

This guideline covers both fabricated or induced illness, and also perplexing presentations where FII may be one of the differential diagnoses. Other differential diagnoses for perplexing presentations include: a true medical cause; parental overanxiety or inexperience; mental illness in parent affecting their perception of child's symptoms. FII overlaps with emotional and physical abuse.

FII involving deliberate deception of medical services by parent/carer, and high risk to the child, is relatively rare. It is important to recognise it and act on it, because it is a potentially lethal form of abuse. In these cases, very prompt action may be required.

The range of symptoms and body systems involved in the spectrum of PP/FII is extremely wide. Children may present to a correspondingly wide range of medical services, spanning primary, secondary and tertiary care.

In all cases it is helpful to focus on keeping the child safe, avoiding harm, and minimising any impact on the child's health and development. In the USA the term "medical abuse" is used [2]. This emphasises that much of the harm is actually done by "duped" professionals". An important part of the approach is therefore to limit or control the health response, through avoiding unnecessary investigation or treatment.

Table 1 - Key terms

| Perplexing Presentations (PP) |

| Presence of alerting signs when the actual state of the child's physical/ mental health is not yet clear but there is no perceived risk of immediate serious harm to the child's physical health or life. |

| Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII) |

| FII is a clinical situation in which a child is, or is very likely to be, harmed due to parent(s') behaviour and action, carried out in order to convince doctors that the child's state of physical and/or mental health or neurodevelopment is impaired (or more impaired than is actually the case). FII results in emotional and physical abuse and neglect including iatrogenic harm. |

| Unexplained Symptoms (MUS) |

| The child's symptoms, of which the child complains and which are genuinely experienced, are not fully explained by any known pathology but with likely underlying factors in the child (usually of a psychosocial nature), and the parents acknowledge this to be the case. The health professionals and parents work collaboratively to achieve evidence-based therapeutic work in the best interests of the child or young person. MUS can also be described as 'functional disorders' and are abnormal bodily sensations which cause pain and disability by affecting the normal functioning of the body. On occasion, MUS may include PP or FII. Helpful guidance is available [3],[4] |

Taken from the RCPCH Guidance published 20215

2. When to consider FII

FII should be considered if a child is being presented as ill when they are not, or as more ill than is actually the case, because of the parent or carer's report or action (usually the mother). Often there is discrepancy between parental accounts of illness and observations of professionals, and puzzlement within the health team.

Although life-threatening FII is rare, presentations where FII should be considered are common in both primary and secondary care settings.

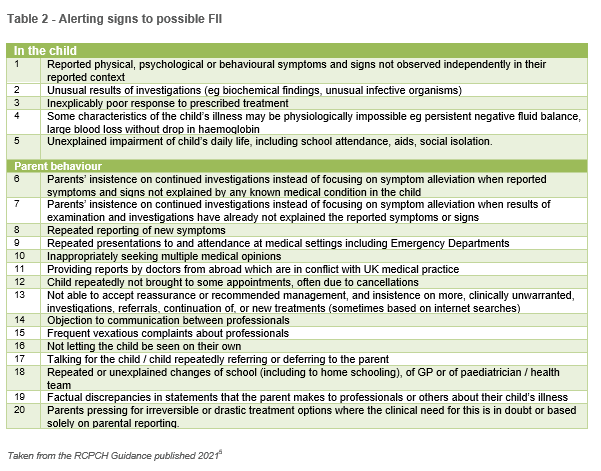

FII is not a diagnosis of exclusion, and should be considered when alerting signs for FII are present (see Table 2 - Alerting signs to possible FII) although note that some of these may occur in genuine medical presentations).

"The essence of alerting signs is the presence of discrepancies between reports, presentations of the child and independent observations of the child, implausible descriptions and unexplained findings or parental behaviours. Alerting signs may be recognised within the child or in the parent's behaviour. A single alerting sign by itself is unlikely to indicate possible fabrication".

RCPCH 20215

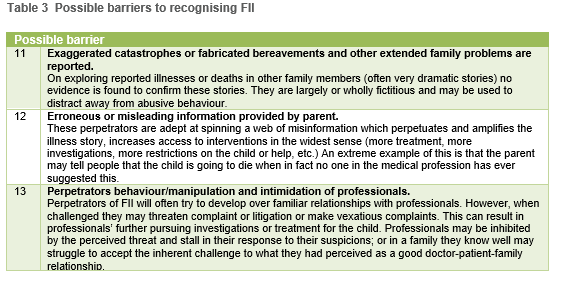

Note possible barriers to recognising FII (Table 3 Possible barriers to recognising FII).

There may be a number of explanations for these circumstances which can include undiagnosed or unusual medical conditions; each requires careful consideration and review.

Concerns may also be raised by other professionals who are working with the child and/or parents/carers who may notice discrepancies between reported and observed medical conditions, such as the incidence of fits.

Professionals who have identified concerns about a child's health should discuss these with the child's GP or consultant paediatrician responsible for the child's care.

If any professional has concerns about a situation being indicative of fabricated or induced illness, then these should be discussed with their child protection lead.

Table 2 - Alerting signs to possible FII

Table 3 - Table 3 Possible barriers to recognising FII

Adapted with permission from City of York and North Yorkshire Safeguarding Children Boards' Fabricated and Induced Illness Multi-Agency Practice Guidance6. This is based on a Serious Case Review by Cumbria Child Protection Committee in 20047. Numbers from the tables can be used in the chronology template (Appendix A: FII Chronology Template).

3. Why is it important to recognise and respond to FII?

It is important to recognise and respond appropriately to FII because children are harmed and sometimes killed by it.

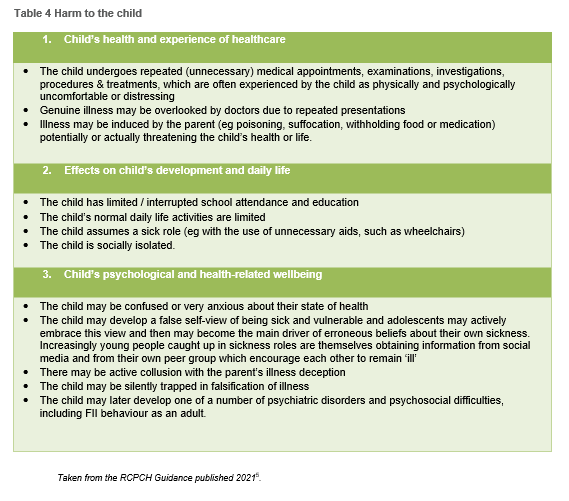

The child can be harmed directly both physically and emotionally (through illness induction and taking on a sick role) and indirectly due to the medical response (where the child suffers unnecessary examinations, investigations, procedures and treatments). This results in:

- Unnecessary painful, harmful investigations / procedures;

- Morbidity/Death;

- Chronic invalidism;

- Actual disease;

- Significant psychological damage;

- FII behaviour as an adult.

Early case series reported significant risks of serious illness and death (e.g. in a review of 451 cases, 6% died and 7.3% had long term or permanent injury [8]). It is likely that these significant risks apply to severe cases (as considered within the 'Red pathway' in this document), rather than the whole spectrum of potential FII. Harm to the child can be summarized under the following 3 areas: health and experience of healthcare; development and daily life; psychological health and wellbeing (see Table 4 - Harm to the child).

Table 4 - Harm to the child

With illness induction comes further heightened risk:

- The pain and distress of induced illness, including the possibly severe physical abuse or starvation.

- A significant risk of death (around 10% in some studies; though there is likely to be selection bias).

- A risk of under-treatment for real conditions.

4. Overall approach to FII

FII is a form of abuse, and the usual child protection procedures apply. Children who are suspected to have illness fabricated or induced require coordinated help from a range of agencies. In contrast to work with other forms of abuse, it may be important and appropriate not to share information or seek consent from the carers at times, since this may put the child at risk.

For Perplexing Presentations, a key step is to ascertain the child's current state of health and daily functioning, define areas of continuing uncertainty, and the nature and level of any harm to child.

Consultation with peers or colleagues in other agencies is an important part of the process of making sense of the underlying reasons for these signs and symptoms. The characteristics of fabricated or induced illness are that there is a lack of the usual corroboration of findings with signs or symptoms or, in circumstances of diagnosed illness, lack of the usual response to effective treatment. It is this puzzling discrepancy which alerts the medical staff to possible harm being caused to the child.

5. Early Identification and Intervention

Early help is an approach to providing support to potentially vulnerable children, young people and their families as soon as problems start to emerge (e.g. see local early help guidance). The principle is that it is better to act early in the evolution of a problem or concern, rather than wait until it becomes obvious and severe. This may be applicable to children where FII is unlikely and the risk low, or where concerns are not substantiated. This also helps provide good clear documentation on attempts to support and advise carers.

6. Adverse Childhood Experiences

When working with children and their families where there are perplexing illnesses or concerns about fabricated or induced illness, professionals should explicitly explore whether the child is currently experiencing, or has previously experienced, adverse childhood experiences such as physical, sexual or emotional abuse, neglect, domestic abuse, child sexual or criminal exploitation, bereavement, parental/caregiver alcohol or drug misuse, severe parental mental health issues, or a parent going to prison. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) such as these can have a detrimental impact on the physical, mental and emotional wellbeing of a child. Professionals should also be mindful that parents and caregivers may themselves have experienced adverse childhood experiences.

7. Medical Evaluation

Where there are concerns about possible FII, the signs and symptoms require careful medical evaluation for a range of possible diagnoses. Agree a lead clinician to do this. Referral to a specialist paediatrician may be needed for review of specific symptoms.

If several consultant paediatricians are involved, a lead consultant should be agreed between them (usually the person most involved in the area where FII concerns are manifesting). If there is difficulty identifying a lead clinician, this should be discussed with the Named Doctor who will advise who should take on this role.

In general the following should be considered:

- Professional consensus about child's current state of health and daily functioning, areas of continuing uncertainty, nature and level of harm to child;

- Collation of all health service involvement;

- Verify all reported diagnoses, with (if necessary) paediatric opinion on specific symptoms;

- Explore parents' and child's views, fears, beliefs, wishes;

- Explore siblings' health and family functioning;

- Chronology;

- Preserve evidence (if relevant);

- Clear report from all;

- Multi-Agency meeting - may include social care;

- Consider early help / support / clear guidance to parents;

- Clear Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan agreed with parents;

- Review outcome of plan;

- Discussion with named / designated doctors;

- Discussion with or referral to social care;

- If admission needed, requires careful planning.

Where, following any investigations (if needed), a reason cannot be found for the reported or observed signs and symptoms of illness, further specialist advice may be required.

Parents should be kept informed of further medical assessments / investigations/tests required and of the findings. Normally the consultant paediatrician will tell the parent(s) that they do not have an explanation for the signs and symptoms and record the parental response.

Concerns about the reasons for the child's signs and symptoms should not be shared with parents if this information would jeopardise the child's safety and compromise the child protection process and/or any criminal investigation. See Working Together to Safeguard Children [9] and relevant national and local safeguarding guidance.

A diagnosis of FII may take a considerable amount of time, including collation of information, formulating a plan and communicating that to the parents, and then implementing the plan and monitoring progress.

8. Chronologies

The purpose is to build a clear picture of all potentially relevant events in the child's life, with analysis, to help make a judgement on the nature and level of risk to the child. Chronologies can be time consuming to compile, and this process, although still very important, should not delay assessment of current functioning and decisions about management. Service managers should ensure that the lead clinician has sufficient time to compile the chronology.

Key Points

- Use Appendix 1: FII Chronology Template;

- Summarise key information – don't just replicate the child's health record;

- Pay particular attention to the specific concerns that have been raised about the child;

- Clearly state what has been said, by whom and to whom;

- Record what has been reported or observed and whether this was observed by professionals;

- Record the source of information e.g. 'History taken from Mother';

- Write in a way that can be understood by colleagues from other non-medical or professional backgrounds.

- Where appropriate, condense a large amount of information into short summary sentence. e.g. 'John was on the ward between 1 June and 4 June there are no recorded incidents of diarrhoea.'

- The comments section of the chronology can be used to highlight where there are particular 'warning signs' as identified in Table 2 - Alerting signs to possible FII.

- Add comments to entries as relevant e.g. "mum presented him with wheeze - no signs seen".

8.1 Timescales

Chronologies should go back as far as possible. In some instances a child may be said to have had a condition for many years. It is important where possible to confirm or refute specific information e.g. where a child is said to have been given a specific diagnosis, evidence of that diagnosis should be sought. Where evidence is not found, the chronology should show that evidence has not been located.9. Evaluating Risk – The Red and Amber Pathways

See also Appendix C: Red and Amber Pathways

Where FII is considered to be a possibility, the risk of serious, immediate harm to the child should be evaluated (see Appendix C: Red and Amber Pathways and Table 2 - Alerting signs to possible FII):

Red pathway

Follow this pathway if risk of serious harm, or evidence of illness induction or deception:

- Presentation is a life threatening symptom e.g. turning blue, fits;

- Evidence of deception;

- Evidence of physical actions by carers to produce an illness picture (interfering with reports, specimens, investigations, withholding medications or food, poisoning).

Also take account of the alerting signs in Table 2 - Alerting signs to possible FII.

In this group it will often become relatively clear that an illness is being fabricated or induced, especially as information from various sources is assembled.

Examples

- Inducing symptoms e.g. a rash through application of chemical to the skin; smothering until loss of consciousness; poisoning e.g. through giving excessive salt by mouth or nasogastric tube; injecting insulin;

- Fabricating or tampering with investigation processes to produce abnormal results e.g. false data on charts; warming thermometers; adding blood to urine;

- Interfering with treatment processes and equipment: e.g. withholding or substituting medication; infecting intravenous lines; turning oxygen down or off; tampering with ventilation equipment.

Amber pathway

Follow this pathway if low risk of serious harm, no evidence of illness induction or deception:

- Symptoms or concerns are not serious or life-threatening;

- Symptoms or concerns relate only to what the parent/carer is saying or reporting, not to physical actions;

- There is no evidence of deception or falsification, although there may be concern about it.

Also take account of the alerting signs in Table 2 when judging level of risk.

In these children the presentations are puzzling. Much of the harm relates to medical over-investigation or treatment, which can be minimised through following this pathway. The pathway is intended to help clarify, address and contain the concerns.

Examples

- Unexplained medical symptoms;

- Children whose parents/carers are excessively anxious, leading to apparent exaggeration of symptoms and excessive reliance on support from health professionals.

The various modalities of FII are not mutually exclusive and may occur together. In practice red and amber pathways may overlap. If in doubt, follow the red pathway.

10. Red Pathway – Probable FII

Immediate Action

(Also see 'Red pathway' on Appendix C: Red and Amber Pathways and Section 9, Evaluating Risk – The Red and Amber Pathways).

Ensure Safety

- If there is immediate or potential serious threat to the child (e.g. include tampering with medical equipment, administering harmful substances, withholding or switching treatments, evidence of smothering), take urgent steps to secure the child's safety and prevent further harm;

- If not already an in-patient, consider immediate admission via ambulance (not allowing carers to bring child in alone), or other action to ensure the child's safety;

- Consider whether the child is in need of immediate protection and measures to reduce immediate risk.

Escalate and Refer

- If in hospital, escalate to the most senior medical and nursing staff on site, call police immediately and secure any evidence (e.g. feed bottles, giving sets, nappies, blood/urine/vomit samples, clothing or bedding if they have suspicious material on them). Inform the consultant;

- An urgent referral should be made to Children's Social Care Services, who should make a rapid decision and respond immediately. The safety of siblings needs to be considered. Refer to the police. An emergency protection order or police protection powers may be needed;

- Usually an urgent strategy meeting will be arranged which must include the paediatrician with primary responsibility for the case.

Review Management

- Review medical management plans in the light of the new information. Some planned investigations, procedures or treatments may now be inappropriate;

- This may include stopping administration of a harmful substance or inappropriate treatment, replacing equipment, or taking specimens for toxicology.

Preserve evidence

- Keep any substances or equipment or clothes that might constitute evidence for a later police investigation in secure storage (such as a controlled drugs cabinet / lines / bedding);

- Ideally these should be locked away by two professionals working together to preserve chain of evidence or given to police.

Identify lead clinician

- Identify which clinician will take a lead for the health aspects of the process. For inpatients, this will be the lead consultant managing the patient.

Seek safeguarding advice

- Advice should be taken at the earliest opportunity from the Named or Designated doctor for children's safeguarding, and the relevant safeguarding team(s) should be alerted (this could be the hospital safeguarding team, or the area team, depending on setting).

Keep thorough records

- Events should be documented in detail, along with professional details of all staff involved. Document concerns in the child's health records e.g. 'this unusual constellation of symptoms, reported but not independently observed, is worrying to the extent that, in my opinion, there is potential for serious harm to the child'). This is important in case the child is seen by other clinicians who are not aware of the concerns.

Don't confront parents

- Confronting parents with concern about FII is best avoided at this point. It may sometimes increase risk to the child, or compromise any criminal or safeguarding process. Discussions must take place with children's social care/police about who is going to inform the parents and when it is safe to do so. This may be agreed at the strategy meeting.

Referral and Further Action

Referral

- FII is a form of child abuse so usual procedures apply. A referral should be made to Children's Social Care Services and the Police in accordance with local Referral Procedure. A rapid decision and response is required (same day). A strategy meeting should be convened involving appropriate professionals (health, social care, police, and consider legal and education).

Strategy Meeting

See West Yorkshire Consortium guidance for further information.

- The strategy meeting should also consider: level of risk to the child and any siblings; how the child might be given opportunity to share their story; need for further investigations, observations, management; need for a police investigation; information sharing with parents (what should be shared, when, and by whom); needs of carers, particularly after disclosure;

- If the strategy meeting identifies that a professional should talk to the child about what is going on for them, to try to understand the situation, the professional should seek guidance regarding safeguarding procedures first. If the red pathway is being followed, this should be undertaken by someone who is trained in Achieving Best Evidence, and the strategy discussion should plan who will talk to the child, and what questions they should ask, in order to help gather evidence and ensure that best practice guidelines are followed.

Chronologies

- A multi-agency chronology should be compiled as soon as possible, ideally for consideration at the first strategy meeting. This is normally led by the lead paediatrician for the child, or social care. If there is doubt about who will assemble the chronology, advice should be sought from the Named Doctor. A standard chronology template should be used (e.g. see Appendix A: FII Chronology Template). Compiling the chronology should not delay the process.

Observation

- A (further) period of admission may be helpful for closer observation and decisions about management. This should be planned carefully with clear instructions and understanding of issues by nursing and other staff involved. Significant improvement while under close observation may add to the concern about FII;

- Covert video surveillance is almost never necessary, since if indicated, then the threshold for care proceedings will already have been reached. Where it is under serious consideration, senior advice from within health, police and social care should be sought, including involving designated professionals. Any CVS would be carried out by police not health workers.

Outcome of Section 47 Enquiry and Single Assessment

Concerns Not Substantiated

- As with all Section 47 Enquiries, the outcome may be that concerns are not substantiated - e.g. tests may identify a medical condition, which explains the signs and symptoms;

- It may be that no protective action is required, but the assessment concludes that services should be provided to the child and family to support them and promote the child's welfare as a Child in Need, or through early help. In these circumstances, appropriate assessment should be completed and planning meetings held to discuss the conclusions, and plan any future support services with the family;

- It may be appropriate for further management to follow the Amber pathway, including consideration of a Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan (see Section 11 Amber Pathway – Perplexing Presentations (PP)).

Concerns Substantiated and Continuing Risk of Significant Harm

- Where concerns are substantiated and the child judged to be suffering or likely to suffer Significant Harm, an Initial Child Protection Conference may be convened or the child may be made subject to orders e.g. an Interim Care Order.

11. Amber Pathway – Perplexing Presentations (PP)

This pathway should be followed where the child has presented in a perplexing or unusual way and the possibility of fabricated or induced illness is being considered, but the risk of serious harm is low (see Appendix C: Red and Amber Pathways and Section 7, Medical Evaluation). The key is to quickly establish the child's actual current state of physical and psychological health and functioning, and the family context. The parents are told about the current uncertainty regarding their child's state of health, the proposed assessment process and the fact that it will include obtaining information about the child from other caregivers, health providers, education and social care if already involved with the family, as well as likely professionals meetings. Wherever possible this should be done collaboratively with the parents.

- An early decision should be made about whether the Red Pathway would be more appropriate, and this should be kept under review throughout. If in doubt, escalate to the Red Pathway;

- The Amber Pathway is slower paced and may take weeks or months: the urgency and timescale is proportionate to the degree of risk and likelihood of FII;

- Regularly consider whether any of the spectrum of presentations outlined in Table 2 may apply.

Identify lead clinician for the child

- Where multiple professionals are involved, communication can become difficult and mixed messages are likely. It is best to agree one person who will take a lead, usually the responsible paediatrician most involved. They will be the main channel of communication with the parents and lead in decisions about further investigation;

- If the lead clinician is also the Named Doctor, then another clinician will need to undertake this consultative role, possibly the Designated Doctor. This means that safeguarding decisions can be made objectively, free from duress, threats and complaints and the responsible clinician has appropriate support in these challenging cases;

- The lead clinician could be the GP or Children and Young People's Mental Health Services (CYPMHS) consultant, but consider a paediatric referral for an opinion about the specific presenting symptoms. A discussion with Named or Designated Safeguarding professionals may be helpful, according to the nature of the problem and local arrangements. Concerns should be clearly summarized in the referral, including the possibility of FII.

Consult with Named Doctor for safeguarding children (who will inform Designated Doctor as appropriate).

Because these situations can be complex with potentially serious repercussions, the lead clinician should have an early discussion of concerns about Perplexing Presentations or possible FII with the Named Doctor. An opinion from a tertiary specialist may be necessary.

Establish current status

The lead clinician (usually the responsible paediatric consultant) should review the situation and establish the current status with regard to: the child's health and wellbeing; the parents' views; and the child's view (if old enough). Provide signposting advice for children, young people and their parents on where to access more information or support.

Child's health and wellbeing

- Collate all current medical/health involvement in the child's investigations and treatment, including from GPs, other Consultants, and private doctors, with a request for clarification of what has been reported and what observed. (This is not usually a request for a full chronology, which would need to include all past details of health involvement and which is often not relevant at this point);

- Ascertain who has given reported diagnoses and the basis on which they have been made, whether based on parental reports or on professional observations and investigations;

- Consider inpatient admission for direct observations of the child, including where relevant the child's input and output (fluids, urine, stool, stoma fluid as applicable), observation chart recordings, feeding, administration of medication, mobility, pain level, sleep. If discrepant reports continue, this will require constant nurse observations. Overt video recording may be indicated for observation of seizures and is already in widespread use in tertiary neurology practice to assess seizures (which must be consented to by parents);

- Consider whether further definitive investigations or referrals for specialist opinions are warranted or required;

- Obtain information about the child's current functioning, including: school attendance, attainments, emotional and behavioural state, peer relationships, mobility, and any use of aids. It is appropriate to explain to the parents the need for this. If the child is being home schooled and there is therefore no independent information about important aspects of the child's daily functioning, it may be necessary to find an alternative setting for the child to be observed (e.g. hospital admission).

Parents' views

- Obtain history and observations from all caregivers, including mothers and fathers; and others if acting as significant caregivers;

- If a significant antenatal, perinatal or postnatal history regarding the child is given, verify this from the relevant clinician;

- Explore the parents' views, including their explanations, fears and hopes for their child's health difficulties;

- Explore family functioning including effects of the child's difficulties on the family (e.g. difficulties in parents continuing in paid employment);

- Explore sources of support which the parent is receiving and using, including social media and support groups;

- Ascertain whether there has been, or is currently, involvement of early help services or children's social care. If so, these professionals need to be involved in discussion about emerging health concerns;

- Ascertain siblings' health and wellbeing;

- Explore a need for early help and support and refer to children's social care on a Child in Need basis, where appropriate depending on the nature and type of concerns, with agreement from parents.

Child's view (if appropriate developmental level and age)

- Any professional seeking the views of a child should first familiarise themselves with safeguarding guidance to ensure this is considered;

- Explore the child's views with the child alone (if of an appropriate developmental level and age) to ascertain:

- The child's own view of their symptoms;

- The child's beliefs about the nature of their illness;

- Worries and anxieties;

- Mood;

- Wishes.

- Observe any contrasts in verbal and non-verbal communication from the child during individual consultations with the child and during consultations when the parent is present;

- Some children's and adolescent's views may be influenced by and mirror the caregiver's views. The fact that the child is dependent on the parent may lead them to feel loyalty to their parents and they may feel unable to express their own views independently, especially if differing from the parents;

- Consider use of 'Being Me' and 'Me first' resources to help children and young people to share who they are, how they are feeling and what support they would like. These resources have been co-designed and developed with children and young people.

Reach a multi-professional consensus

Multi-professional meeting

- Ascertain child's current state of health and daily functioning:

- Collate all current health service involvement;

- Verify all reported diagnoses, who has given them, and on what basis;

- Identify whether children's social care involved;

- Explore parents' and child's views, fears, beliefs, wishes;

- Explore siblings' health and family functioning.

- Obtain consensus from all professionals involved, including education and children's social care (if already involved) on the following:

- Child's current state of health;

- Areas of continuing uncertainties;

- Nature and level of harm to child.

There may need to be one or more professionals' meetings to gather information. These can be virtual meetings. Where possible, families should be informed about these meetings and the outcome of discussions as long as doing so would not place the child at additional risk. Care should be given to ensure that notes from meetings are factual and agreed by all parties present. Notes from meetings may be made available to parents, on a case by case basis and are likely to be released to them anyway should there be a Subject Access Request for the health records.

Although this meeting can be chaired by the lead clinician, consider whether it might be better chaired by the Named Doctor (or a clinician experienced in safeguarding with no direct patient involvement) to ensure a degree of objectivity and to preserve the direct doctor-family relationship with the responsible clinician. Parents should be informed about the meeting and receive the consensus conclusions with an opportunity to discuss them and contribute to the proposed future plans (see below).

A consensus needs to be reached in a meeting between all professionals about the following issues:

Either

- That all the alerting signs and problems are explained by verified physical and/or psychiatric pathology or neurodevelopmental disorders in the child and there is no FII (false positives);

- Medically Unexplained Symptoms from the child free from parental suggestion;

- That there are perplexing elements but the child will not come to harm as a result;

Or - That any verified diagnoses do not explain all the alerting signs;

- The actual or likely harm to the child and or siblings;

And agree all of the following: - Whether further investigations and seeking of further medical opinions is warranted in the child's interests;

- How the child and the family need to be supported to function better alongside any remaining symptoms, using a Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan (see below for details);

- If the child does not have a secondary care paediatric Consultant involved in their care, consideration needs to be given to involving local services;

- The health needs of siblings;

- Next steps in the eventuality that parents disengage or request a change of paediatrician in response to the communication meeting with the responsible paediatric consultant about the consensus reached and the proposed Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan.

Detailed chronology and multi-professional working

- Professionals involved should compile their own chronologies and agree who is responsible for merging these. Advice can be sought from named professionals. See 'Chronologies' section above, and the template in Appendix A: FII Chronology Template. Compiling a full chronology should not delay the process;

- The aim is to build up a clear understanding of all the child's health presentations, and who is involved. It is helpful to talk to the child about their own concerns, anxieties and beliefs about their symptoms. Reports and records of other professionals should be sought, including the child's GP, who may have important background knowledge. It may be appropriate to approach school or nursery. It is important to build up a full picture of the child's daily functioning including school, activities, aids etc.;

- All of this should be done openly with parents where possible unless this would put the child at risk. Parents will usually be pleased that their concerns are being taken seriously and information is being gathered together to make a thorough assessment. Lack of engagement with the process, or refusal for further information to be sought, would increase concern.

Consider involving social care

- Not always necessary at this point, but appropriate if FII thought quite likely, or other social issues have been identified, or a social care perspective might help towards understanding the child's problems;

- Consider carefully whether to inform parents at this stage, and if in doubt, take advice from Named professionals. The child's welfare and safety is the overriding priority;

- Early help approaches may be applicable and helpful.

Involve and Inform the GP

- Keep GPs fully informed and so they can support children and their families as appropriate as well as work in partnership with other professionals involved to ensure the best outcomes for children.

Agree a Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan

An example Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan template has been provided in Appendix B: Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan Template. This plan should be developed and implemented, whatever the status of children's social care involvement is. It requires a coordinated multidisciplinary approach and negotiation with parents and children and usually will involve their attendance as appropriate at the relevant meetings. The Plan is led by one agency (usually health) but will also involve education and possibly children's social care. It should also be shared with an identified GP. It must specify timescales and intended outcomes.

- Agree who in the professional network will hold responsibility for coordinating and monitoring the Plan, and who will be the responsible lead clinician (usually a secondary care paediatrician). This person's employing organisation should ensure the clinician has adequate time and resources for this task to be fulfilled;

- Consider what support the family require to help them to work alongside professionals to implement the Plan (e.g. psychological support and / or referral to children's social care for additional support);

- The Plan requires health to rationalise and coordinate further medical care and may include:

- Reducing/stopping unnecessary medication (e.g. analgesics, continuous antibiotics);

- Resuming oral feeding;

- Offering a graded return to normal activity (including school attendance).

- Psychological input may be helpful;

- Social care or other agencies may also be involved.

Avoid medical testing /treatment that is not clearly indicated, restore normality

- Harm to the child can be mainly through the excessive response of (usually health) professionals, in terms of over-investigation and treatment;

- Aim to draw a line and reach the point where parents can be told "We have investigated enough";

- This may need multi-professional or multi-speciality discussion. If a further opinion is sought, they need to be aware of the context, and investigations already done;

- Where possible, aim to restore the child's daily functioning to nearer normality.

A period of admission may be helpful for closer observation

- Occasionally in cases of medical uncertainty, a period of in-patient admission is helpful to observe in detail what is happening.

- This is arranged transparently with the family, explaining that this is part of good practice in these situations and the ward team will ideally be involved in all the details of the child's care and observation.;

- All staff involved should be clear about the nature of the concerns, and the purpose of the admission, including what is to be particularly observed, and how this should be documented;

- Seek advice from Named professionals.

Support for parents

- Where excessive parental anxiety is part of the presentation, this should be contained through having a lead person, avoiding mixed messages, avoiding continued investigation, appropriate and repeated reassurance (including in writing) and having clear pathways of support (what to do and who to contact if…);

- Attention should be given to the parent(s)' own support networks and mental and physical health, if these are thought to be contributing to anxiety. A referral for mental health support may be appropriate

Communication to parents and child

- Once health consensus has been achieved and a draft Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan formulated, a meeting should be held with the parents, the responsible clinician and a colleague (never a single professional). The meeting will explain to the parents that a diagnosis may or may not have implications for the child's functioning, and that genuine symptoms may have no diagnosis. It is preferable to acknowledge the child's symptoms rather than use descriptive 'diagnoses'. It is often useful to use the term 'issues/concerns' in clinical letters rather than 'diagnoses' in these circumstances;

- The current, as of now, consensus opinion is offered to the parents with the acknowledgment that this may well differ or depart from what they have previously been told and may diverge from their views and beliefs. The draft Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan is explained to the parents, including what to explain to the child and what rehabilitation is to be offered and how this will be delivered. Negotiation about the plan details can take place with the parents at this stage, provided that the final Plan is consistent with the consensus reached by the multi-professional meeting;

- Often the process outlined above has led to clarity amongst all professional involved where they can say to parents "We are confident there is no serious underlying medical problem, and we want to work with you to enable your child to live as normally as possible despite any symptoms". This message should be given positively with constructive planning to limit the impact of on-going symptoms on the child's well-being.

Long term monitoring of progress and when to escalate

- The response to, and progress after, the meeting is key and may further clarify whether this is FII. Careful monitoring is needed for weeks and months afterwards, with an agreement regarding when escalation to a formal safeguarding pathway (the Red Pathway) would be needed. It is important to agree who will monitor progress;

- Outcomes that would increase concerns regarding FII would include: parents wishing to 'sack' the lead clinician and refusing to work with them; attempting to move the child out of area or to a different hospital; refusal to engage with any agreed process; increasing physical symptoms (still without any medical explanation); new or more dangerous symptoms.

12. Roles & Responsibilities in Recognising & Responding to Perplexing Presentations and possible FII*

* This section adapted with permission from City of York and North Yorkshire Safeguarding Children Boards Fabricated and Induced Illness Multi-Agency Practice Guidance[6].

In all cases of perplexing presentations and suspected fabricated and induced illness, advice and support should be sought from the appropriate agency safeguarding lead, or named and designated professionals for safeguarding.

Professionals not from a Health setting including Education/Early years/Early Help/Children's Social Care

- Professionals may have concerns because parents are describing a child's illness or health needs which are not witnessed by the professionals;

- In such situations, professionals should consider the other alerting signs in Table 2 - Alerting signs to possible FII. If they remain concerned or have heightened concerns they should discuss the child with their safeguarding lead;

- If concerns remain, then the child should be discussed with relevant health professionals. This could involve liaison between the service manager and the area Safeguarding Team or the Designated Doctor for Safeguarding Children;

- Consent from the parents to do this should be sought on the grounds that that this is usual practice where a child has an illness which is impacting on their health or development;

- At this stage the concern about possible FII should not be disclosed to the parent/carer. If parents refuse consent for a discussion with health professionals then this should be discussed with the safeguarding lead to consider whether refusal increases the level of concern.

- When a parent/carer reports restrictions or limitations for normal school activities due to reported 'health' issues, it is important this is verified.

Health visitors and school nurses

- If practitioners have concerns that a parent/carer is impairing a child's health, development or functioning by fabricated or induced illness, they should meet with parents/carers or discuss the child's illness, parental concerns and ascertain which other health professionals are involved;

- After discussion it may be that some parents may have misunderstood information, are anxious about their child or have concerns that their child's needs are not being met. This may lead to health-seeking behaviours or exaggeration of symptoms. The practitioner should seek parents/carers' consent to discuss the child with those professionals involved including the consultant;

- Where the practitioner has on-going concerns about FII and the child is already known to other health professionals, then information should be sought from those professionals regarding the medical illness/diagnosis, and advice or an appropriate care plan should be provided - at this point consent is not required;

- Concerns about possible FII must be shared with the other health professionals (including GPs).

Midwives

- Midwives may be alerted to possible FII by mothers' own health-seeking behaviour, history of unusual/unexplained illness, unusual complications of pregnancy, and unexplained deaths of previous children;

- If concerns are raised then previous pregnancy notes should be obtained and the midwife must discuss concerns with their safeguarding lead or a named professional for safeguarding.

General Practitioners (GPs)

- In cases of suspected FII, the GP is likely to have had a higher level of involvement and knowledge of the child and family than other health professionals. GPs' involvement and contribution to the management of FII concerns is essential to ensure that all key information with regard to the child is shared. GPs will also be aware about parental health issues – including both physical and mental health – and these should be taken into consideration as part of any assessment and information sharing;

- If there are concerns about the welfare of a child and FII is a consideration, the child's needs are paramount and the GP has a duty to share any relevant and proportionate information that may impact on the welfare of a child. This includes sharing relevant information about parents and carers as well as the child. GPs are well placed to recognise early symptoms and signs of FII in a child, and as the primary record keeper of all health records, can play a key role in recognising patterns of worrying behaviour from multiple presentations at different settings;

- For children on the Amber pathway, the clinician already leading management (who may be the GP or Paediatrician, or other clinician) may continue as the lead clinician for the FII concern, with advice from the appropriate agency safeguarding lead, or named and designated professionals for safeguarding. Red pathway cases not known to a consultant should normally be referred to a Consultant Paediatrician, Child Psychiatrist or Clinical Psychologist (dependent upon the presenting issues) with expertise in symptoms and signs that are being presented;

- When a referral is made the GP should make it clear about their concerns re possible FII in the referral letter. This letter should not be copied to parent/carers. Timeliness of the referral will depend on presentation. For example if there are signs or symptoms of induced illness such as suffocation or poisoning then same day referral is needed with a concurrent urgent referral to Children's Social Care Services;

- When recording concerns about FII, GPs should ensure that these concerns are recorded within the child's clinical record but that the entry is not visible on online access, as parental awareness of the concern may escalate the risk to the child.

Children and Young People's Mental Health Services (CYPMHS)

Staff within Children and Young People's Mental Health Services (CYPMHS) may also be alerted to concerns about possible FII in the process of evaluating children for mental health and behavioural difficulties.

- Repeated requests for a diagnosis of conditions such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), especially when assessments have ruled out these conditions, should raise the index of suspicion for FII. However, it should be noted that it is not uncommon for parents to request second opinions, and consideration should be made to the fact that there are a number of children who do get a diagnosis of ADHD/ASD when reassessed. A repeat parental request for another medical/Children and Young People's Mental Health Services (CYPMHS) opinion should not automatically trigger an investigation for FII, as this might be inappropriate;

- In Children and Young People's Mental Health Services (CYPMHS) cases of FII there have usually been many requests for assessments for mental health diagnoses with repeated requests for second/third/fourth opinions;

- Initial concerns about a child's presentation should be shared with the Paediatrician or GP that referred the patient and other relevant health professionals.

Adult Mental Health Services

Adult mental health staff may become concerned about the welfare of a child in relation to possible FII. These concerns may be increased if a patient who is a parent is known to fabricate or induce illness in themselves, although this can exist within the parent's presentation and not the child's. If an adult mental health worker has any concerns of this nature about a child's welfare they should be discussed with the appropriate safeguarding lead or named professional for safeguarding. Confidentiality may need to be breached without consent in order to protect the child as there is a statutory obligation on all professionals to act in the best interests of children in order to safeguard children.

Allied Health Professionals

If staff have concerns about FII in children they are providing therapy and care for they should discuss with the Safeguarding Children Team within their Trust and GP or the practitioner who referred to their service. They should also discuss with their clinical manager.

Consultant Paediatricians, Consultant Child Psychiatrist or Consultant Clinical Psychologist

All Red Pathway cases of suspected FII should be led by a Consultant Paediatrician, Consultant Child Psychiatrist or Consultant Clinical Psychologist (dependent upon the concerns). This Consultant should take a lead role in this process, with advice from the local hospital safeguarding team and Named Doctor. During the thorough medical evaluation, the Lead Consultant should obtain information from the GP and other Consultants who have been involved in the child's care. This may include relevant information about the parent's health and the siblings.

Other Consultant Specialists

If another Consultant, other than a Paediatric or Children and Young People's Mental Health Services (CYPMHS) Consultant, has a concern about FII in a child in their care they should refer to a general or community Paediatrician (depending on local arrangements). If there are immediate concerns for the child's safety an immediate referral should be made to Children's Social Care Services.

Designated Professionals for Safeguarding Children

Designated Professionals provide a valuable source of expert advice and support to health care professionals and colleagues from partner agencies. They can offer safeguarding supervision or facilitate professional discussions, particularly where the presenting issues are very complex.13. Resolving Professional Disagreements and Escalation

- Cases where FII is suspected are often complex, and professionals may disagree about the best way forward, either within or across agencies;

- Disagreements are best avoided by an open and thorough approach that involves all professionals working with the child and family from early on, taking careful account of each person's perspective and concerns;

- This is particularly important in professionals'' meetings, where all involved with the child should be present if possible, and the meeting should be chaired by a colleague with experience of FII and chairing difficult safeguarding meetings;

- If professional disagreements arise, these should be resolved or escalated according to local policies.

14. Meeting Minutes

- All meetings about perplexing presentations where FII is being considered as a possible explanation of a child's presentation should be minuted, recording who was present, observations, discussion and decisions reached. For a Strategy discussion Childrens Social care have responsibility for minuting the discussion / meeting. For all other multi-agency meetings it should be agreed who will minute discussions at the start of the discussion / meeting;

- Draft minutes should be circulated by the agency who minuted the discussion / meeting for approval by all present, followed by final agreed minutes. This is important for clarity of process, and because of potential medico-legal or criminal proceedings that may follow.

15. Support

It is important to acknowledge the emotional challenge that involvement in such cases can pose to professionals, and ensure appropriate support strategies. These include:

- A team approach – no professional should carry this alone. Being able to discuss and share with colleagues, with acknowledgement of the challenge and potential distress involved can be positive and helpful;

- Working with experienced professionals (safeguarding leads, Named and Designated Professionals, Safeguarding teams);

- Consider separation of the clinical leadership of the case from the safeguarding oversight;

- Complaints departments and Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) should understand and take account of the complex dynamics involved in such cases, with advice from Named and/or Designated professionals;

- Managers should ensure appropriate time and resources are available for staff doing this work – it can be very time-consuming as well as emotionally draining;

- Employing organisations should offer occupational health or counselling support to staff dealing with such cases;

- Use of appropriate local escalation mechanisms where there is lack of agreement between professionals.

16. References and Key Sources

This guidance is based on the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) 2021 publication entitled 'Perplexing Presentations (PP) /Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII) in Children'[5], along with the previous West Yorkshire guidance published in 2019. It also takes account of other relevant documents including: 'Safeguarding Children in Whom Illness is Fabricated or Induced' (HM Government 2008) [10]; 'Working Together to Safeguard Children'[9]; the 'RCPCH Child Protection Companion' (2013) [1]; work by Danya Glaser and colleagues [11-13].

- Perplexing Presentations (Including FII). In: RCPCH Child Protection Portal;

- Roesler TA, Jenny C. Medical Child Abuse: Beyond Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy. Itasca, IL 60143: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008;

- Blake L, Davies V, Conn R, Davie M. Medically Unexplained Symptoms (MUS) in Children and Young People. London: Paediatric Mental Health Association and Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2018:1-49;

- Heyman I. Mind the gap: integrating physical and mental healthcare for children with functional symptoms. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(12):1127-1128. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2019-317854;

- Perplexing Presentations (PP) / Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII) in Children RCPCH Guidance. London: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; 2021:1-44;

- Anonymous. Fabricated and Induced Illness: Multi-Agency Practice Guidance. York: City of York and North Yorkshire Safeguarding Children Boards; 2017:1-20;

- Postlethwaite RJ, Benson E, Quinn K, et al. Report to Cumbria Child Protection Committee of Events Leading to the Death of Michael Who Was the Victim of Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII) (Formerly Known as Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy). Cumbria: Cumbria Child Protection Committee; 2004:1-106;

- Sheridan MS. The deceit continues: an updated literature review of Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(4):431-451. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00030-9;

- Anonymous. Working Together to Safeguard Children. London: HM Government; 2018:1-11;

- Government H. Safeguarding children in whom illness is fabricated or induced. Supplementary guidance to Working Together to Safeguard Children. 2008:1-96;

- Bass C, Glaser D. Early recognition and management of fabricated or induced illness in children. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1412-1421. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62183-2;

- Davis P, Murtagh U, Glaser D. 40 years of fabricated or induced illness (FII): where next for paediatricians? Paper 1: epidemiology and definition of FII. Arch Dis Child. April 2018:archdischild–2017–314319–6. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2017-314319;

- Glaser D, Davis P. For debate: Forty years of fabricated or induced illness (FII): where next for paediatricians? Paper 2: Management of perplexing presentations including FII. Arch Dis Child. April 2018:archdischild–2016–311326–6. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2016-311326

Appendix A: FII Chronology Template

Appendix B: Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan Template

Click here to view Appendix B: Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan Template